Home

Contents of one box in the National Slag Collection

Open cast iron ore mining, Romano-British

& just digging

Crafts

comparing excavated sites

Documentary record search

Activity frequency mapping (iron works)

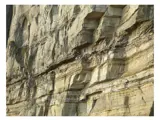

Outcrop of sideritic ore overhanging sandstone

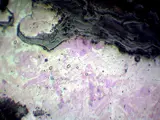

Etched sample of unworked bloomery iron (photomicrograph)

Highly vesicular bloomery slag

experimental archaeology

more comparative studies

Conferences

artefactual evidence

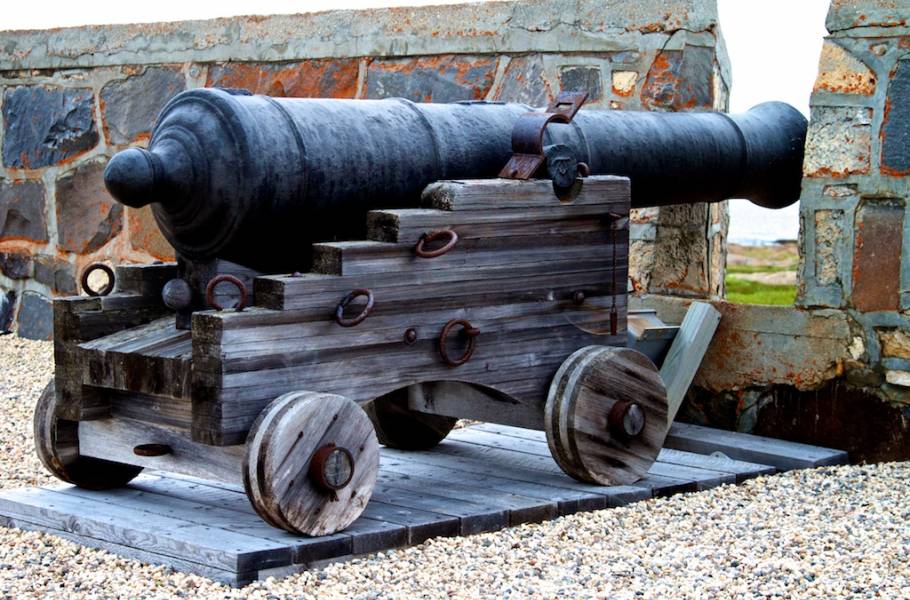

Part of an early blast furnace (Araglin, Ireland)

experimental reconstruction