Home

Etched sample of unworked bloomery iron (photomicrograph)

Outcrop of sideritic ore overhanging sandstone

Conferences

Experimental reconstruction

Comparing excavated sites

Open cast iron ore mining, Romano-British

Recording artefacts in situ

Just digging

Highly vesicular bloomery slag

Artefactual evidence

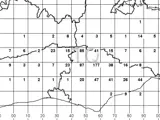

Activity frequency mapping (iron works)

Crafts

More comparative studies

Contents of one box in the National Slag Collection

Documentary record search

Experimental Archaeology

Part of an early blast furnace (Araglin, Ireland)