Journal Contents

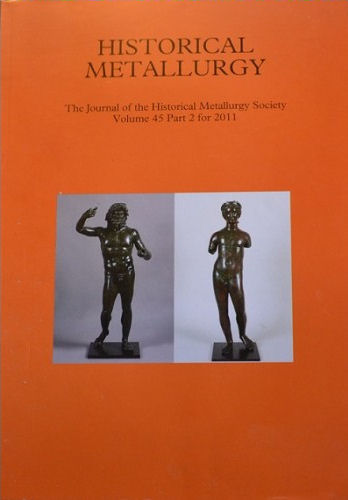

An experimental study of the welding techniques used on large Greek and Roman bronze statues

Aurelia Azema, BenoTt Mille, Patrick Echegut and Domingos De Sousa Meneses

Pages 71-80

There are two key techniques in the manufacture of large Greek and Roman bronze statues. First, the statue is cast in several pieces by the indirect lost-wax process, and then the pieces arejoined by aflowfusion welding process. The principle of ancientflow fusion welding consists ofpouring molten bronze between the bronze pieces to be joined. Our laboratoiy experiments contribute to the understanding of this joining process by studying the thermal and physico-chemical parameters that control the fusion welding of binary copper-tin alloys (bronzes). The results obtained were compared with observations of ancient joins on large bronze statues, but some questions remain unanswered. In particular, whatever experimental conditions were used, we were unable to produce a weld longer than a few centimetres, whereas some ancient welds can be up to a metre long. The use of a ‘magic’ additive, which could act as a welding flux is thus suspected.

An 8th-9th century AD iron smelting workshop near Saphim village, NW Lao PDR

Thomas Oliver Pryce, Chanthaphilith Chlemsisouraj, Valery Zeitoun and Hubert Forestier

Pages 81-89

A rare example of an organised industrial workshop is reported, from the environs of the ethnic Lamet village of Saphim in Luang Namtha Province in NWLao PDR. The archaeological site contains the remains of seven sub-circularfurnaces in a distinct linear arrangement. Two furnaces were excavated, one of which was largely complete and provided evidence for a forced blast, multiple use, slag-tapping iron smelting operation. Six thermoluminesence dates derivedfrom wall fragments provide a date range from 621±270 to I181±170 AD, indicating that the workshop relates to production in the historic pre-European contact period. The organised layout of the furnaces is suggestive of either simidtaneous production or a production sequence, rather than the distribution expected of chronologically superposedproduction within dating resolution limits. A multi-furnace workshop level of supply was probably in excess of local demand, and thus contemporary regional comparisons for social contexts of iron production and exchange networks are explored.

Beyond Wayland - thoughts on early medieval metal workshops In Scandinavia

Ny Bjorn Gustafsson

Pages 90-101

This paper reflects on and summarises the current state of research on early medieval (750-1100 AD) metal workshops in Scandinavia by way of examples from workshops and metalworking sites recovered via archaeological excavations and surveys over the last 30 years. A critique is presented of a number of features which occur perennially in Scandinavian archaeometallurgical presentations, such as the tendency to overemphasise the importance of written accounts and the common habit of over-interpreting archaeometallurgical finds

Iron in 1790: production statistics 1787-96 and the arrival of puddling

Peter King

Pages 102-133

The 1780s and 1790s were a period of great change in the British iron industry. These decades saw a rapid transition from most bar iron being made with charcoal in finery forges and hammers to the use of reverberatory furnaces fuelled with coal, and the iron being rolled into bars instead of hammer forged. This change is illustrated by a series of lists, of which the fullest and most important was probably compiled in 1790, but partly updated in 1794. The list provides good evidence of the spread ofpotting and stamping and of a process to recycle scrap iron, but has a few suiprising omissions. The subsequent successful adoption of puddling depended on the production offiners’ metal, developed at Merthyr Tydfil in about 1791. This only gradually replaced the stamping process, which was the first to produce good bar iron without charcoal.

There are no reviews yet.